UMW Professor Helps Shed Light on Rapid Climate Change in Greenland 8,200 Years Ago

February 10, 2026

University of Montana Western professor Dr. Spruce Schoenemann has led a team of researchers that has uncovered new details about one of the most abrupt climate events of the last 12,000 years. The study, recently published in "Paleoceanography and Paleoclimatology", focuses on the 8.2 ka Event, a sudden cooling that occurred roughly 8,200 years ago during the final stages of the last major ice age.

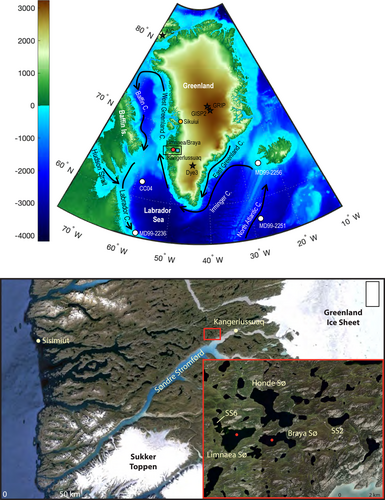

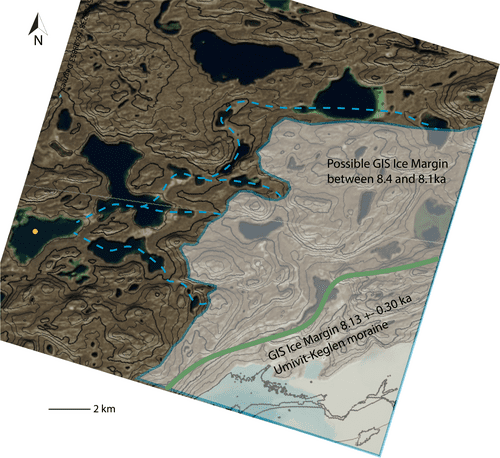

While the 8.2 ka Event has been studied for decades using ice cores and ocean sediments, Schoenemann and collaborators examined it from a fresh perspective: lake sediments near the Greenland Ice Sheet. Their work helps scientists understand how temperatures and local environments changed close to the ice margin, offering a new layer of detail on how abrupt climate shifts can unfold on land.

The team combined multiple types of evidence preserved in the sediments. They studied chemical signatures from algae that lived in the lakes thousands of years ago and measured isotopes that reflect past temperature and water conditions. Together, these records allowed the researchers to estimate lake temperatures and track how the region’s environment responded during the 8.2 ka cooling.

“One of the unique aspects of this research is the combination of measuring both the carbonate isotopes and alkenones together, as prior studies tended to focus on just one proxy type (e.g., isotopes, chironomids, alkenones, leaf waxes, or magnetic susceptibility),” said Schoenemann. “Together, the alkenones provide inferred lake water temperatures, which can be used to back out the original water isotope values that the original sediment carbonates formed from. This provides a broader picture of what aspects of the climate system were responding to the disintegration of the LIS, meltwater incursions to the Labrador Sea, and how the ice sheet adjusted rapidly.”

Their results suggest that cooling near the ice sheet margin may have been more intense than previously recognized. In some cases, lake records indicate temperature drops larger than those recorded in central Greenland ice cores. The findings also show that the timing and severity of the cooling varied across the region, influenced by factors such as seasonal changes and proximity to the ice sheet.

Scientists believe the 8.2 ka Event was triggered by the collapse of the Laurentide Ice Sheet, which once covered much of North America. As the ice sheet broke apart, huge amounts of freshwater from glacial lakes drained into the North Atlantic. This sudden influx likely disrupted major ocean currents that carry heat north, causing rapid cooling in Greenland and parts of the Northern Hemisphere.

Schoenemann worked closely with faculty and students at the University of Washington’s Earth and Space Sciences and Oceanography departments, bringing together expertise in climate modeling, geochemistry, and sediment analysis.

“This work has been over a decade in the making, with the initial retrieval of the Greenland sediment cores occurring back in 2012 and then years developing novel techniques to measure the very low concentrations of alkenones and clumped isotopes,” said Schoenemann. “It’s a testament to persevering in the face of challenging analytical techniques.”

Their combined work provides a more complete picture of the event, linking ice sheet collapse, ocean circulation changes, and regional cooling.

Understanding abrupt climate events like the 8.2 ka cooling is increasingly relevant today. Although the causes of past and present climate change differ, studying how the climate system responded to sudden disturbances in the past helps scientists better understand its complexity and sensitivity.

“The implications of this research are that the climate system can change relatively rapidly, even on geologic timescales, and the glacier melt, ice margin retreat, and warm ocean water incursions that we are observing in Greenland from human-caused warming will likely accelerate over the coming decades,” Schoenemann said.

These insights are critical for improving climate models and anticipating how modern changes, particularly in polar regions, may unfold in the future. As paleoclimate researchers continue to uncover evidence preserved in ice, sediments, and other natural archives, studies like this one offer valuable context for understanding both Earth’s past and the challenges posed by rapid climate change today.

Read the full publication here. For more information, contact Dr. Spruce Schoenemann at [email protected].